The Female Orphan Scheme to Australia in the 1840s

“Morally pure” girls were selected from Irish workhouses for the scheme

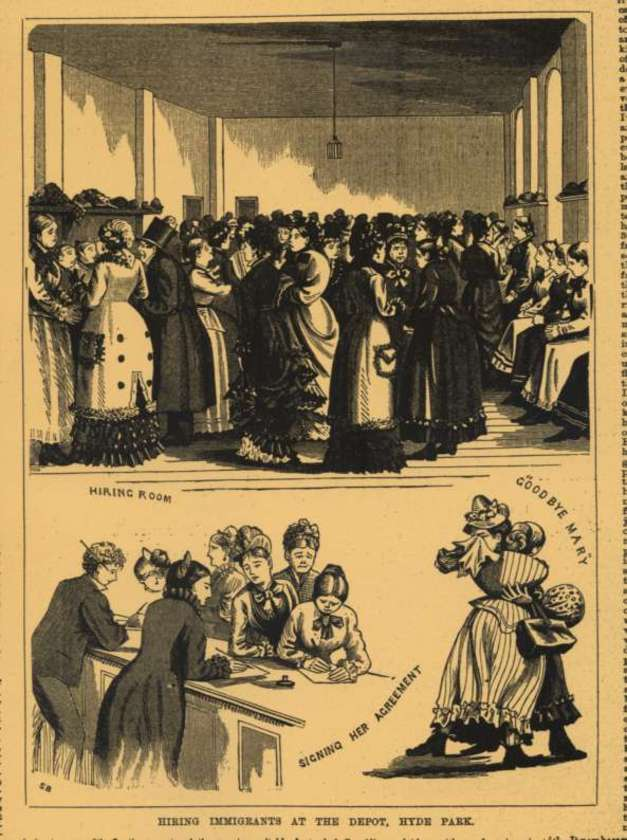

Earl Grey Famine Orphans, Hyde Park depot sent to Australia, c/o Millstreet.ie

Emigration from Ireland in the Nineteenth Century was unique in that the number of women who emigrated rivalled the number of men. This was due largely to the Female Orphan Emigration Scheme to Australia. By the 1840s, the colonial authorities in Australia wanted to recruit female settlers because of the large gender imbalance in the colony (8:1 in favour of men). The Australian authorities funded the transportation costs of females emigrating from Ireland and Britain to Australia. Consequently the scheme received political support from Britain because it cost the government nothing and reduced the rates payable to poor law unions. However, many British girls did not want to immigrate to Australia as the majority of male inhabitants there were convicts. So, attention turned to Irish women.

By 1840 the workhouses in Ireland were full, making such an emigration scheme attractive. The Australian authorities laid down very strict guidelines as to who would be eligible for the scheme. Specifically, the girls had “to be imbued with religion and morally pure”, preferably between the ages of 14 – 18, in good health and posess industrial skills (which would not be possible given the level of education and training provided to workhouse females). Lord Grey (British Secretary of State for the Colonies) was determined that the Emigration Commissioners meet these demands and “in February 1848, they reported to him that there were a large number of well conducted young women to be found amongst the orphans”. Thus, based on this report, suitable workhouse girls were chosen and sent to Dublin or Cork port where they then sailed to Plymouth and subsequently on to Australia.

The Poor Law Commissioners planned this scheme very carefully as they were determined to make it a success so that it could continue in the future. Before setting sail, every female was provided with “an outfit comprised of six shifts, two flannel petticoats, six pairs of stockings, two gowns and two pairs of shoes. Episcopalian girls were to be given a bible and a prayer-book, Protestants a bible and a psalm-book and Catholics a Douay Bible and a prayer-book”. They were also provided handmade wooden boxes of good quality which would hold their belongings. In June 1848 the first ship, called the Earl Grey, carried 185 workhouse females from 10 unions (mainly Ulster) to Australia. Initially, the scheme struggled due to the negative reports about the first arrivals: “Girls from Belfast union were of a disreputable character, being described as ‘beggars and prostitutes’, and were insubordinate during the voyage. It was also reported that the women frequently drank on board, acted inappropriately with the ship staff and that one female had even died during an attempted abortion. Due to the immigrants’ antics and their lack of domestic service experience, the scheme was put on hold.

However, by 1849 a second phase of female emigration from the Irish workhouse was implemented due to increased pressure from the British government on Australian authorities. “Within twelve months 2219 orphans from eighty-eight separate unions had sailed to Adelaide. Port Philip and Sydney”. By May 1850, 4175 female orphans were assisted in emigration to Australia, coming from 118 separate unions around Ireland. The majority of women managed to quickly build new lives, and were snapped up by employers and potential husbands at the ports upon arrival in Australia. However, the authorities found women who arrived without domestic service skills problematic, as domestic service was the main source of employment for the Irish female immigrants.

The scheme ended in 1850 because funds had become harder to obtain and authorities were unhappy with the ‘type’ of women being sent out. While lack of skills and “morality” was an issue, the major reason for the reduced demand for Irish women was religion. Prejudice against Catholics was leveled by the Scottish and Northern Irish Presbyterians who had already settled in the host country, along with other protestant emigrants who arrived later, bringing their prejudices with them from Ireland.

Shelly Mitchell