Emily McManus, Matron of Guy's

The heroism of a young Irish nurse in wartime Britain.

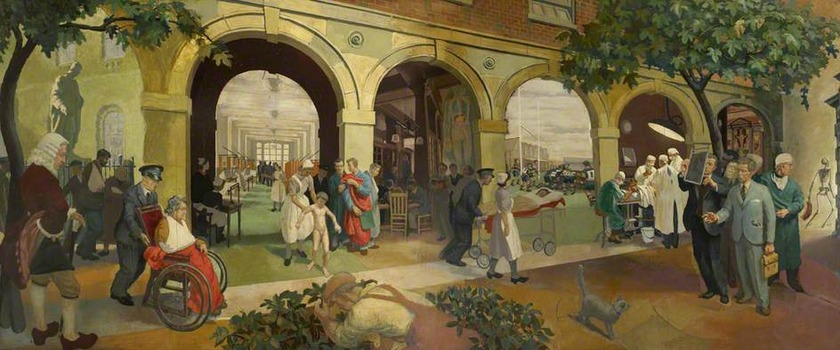

Life at Guy's Hospital' oil by G.Earle Wickham (Guy's and St. Thomas Hospital)

We knew her simply as ‘Miss MacManus’. She was a small, wiry woman who drifted in and out of our young lives in a variety of amusing, bizarre ways. To us, growing up in Mayo in the 1960s, she was puzzling, at times a bit scary, but most of all ‘different’. The upper-crust accent, the tweed outfits, her little green Morris Minor car all added to her intrigue. It was a bit like having our very own Miss Marple fussing about the backroads of Mayo. And, just like Agatha Christie, it took time to pull all the clues together and discover just what a remarkable person she really was.

Miss MacManus was into her 70s when we got to know her. She lived in Pontoon at Terrybaun in a small lakeside house near my aunt Julia and uncle Ernie. We knew she had ended up matron of a famous hospital in London but I found this a bit boring until I came across a book in my aunt’s house, Matron of Guys by E P MacManus. The photographs were what grabbed my attention: France; World War One; Red Cross ambulances grinding through the mud; rows of bandaged soldiers in a vast tented hospital; surgeons around a makeshift operating table, a young Miss MacManus assisting.

Emily Elvera Primrose MacManus, born in 1886, came from a distinguished Mayo family. Although she was born in London, her roots were forever deeply embedded in Mayo, and especially the family’s ancestral home, Killeaden. She said her father had drilled into her young heart that, no matter where she lived or lodged, Killeaden was home.

In 1908, aged 22, she entered Guy’s Hospital in London as a trainee nurse. In the Spring of 1915, as the WWI began to disgorge its litany of maimed, she headed for Northern France as a Nursing Reserve Sister and spent the next three and a half years nursing behind the trenches. Her base station at Etaples grew into a giant hospital city. Nearby, day by day, row by row, a vast military cemetery advanced across the countryside.

Her modesty and humanity seeps through the pages in her accounts of those years. It was the responsibility of the nurses, she said, to create for the wounded an atmosphere of homeliness in the “midst of the mud and blood, dust and death, in which they spent most of their days”. Her insights are fascinating, sometimes disturbing: An Australian band unit filtered in to fetch and carry, lightening everyone’s spirits. “Then, one night” she wrote, “they were no more – a direct hit on their band hut had finished them all”.

On returning to England, she rose up the nursing ranks, becoming the Matron of Guy’s in 1927. Her reputation as a pioneering leader in nursing grew and in 1930 she received an OBE. But all this time, Mayo was calling. Her beloved Killeaden was now closed, so she began to build a little fishing lodge some 20 miles away. She was there, amongst mountains and trout lakes, when news reached her of the outbreak of the Second World War.

In December 1940, during the Blitz, Guy’s had to be evacuated for the first time since opening in 1725. Miss MacManus replied stoically that it was “sad, but not overwhelming, for the spirit of the hospital cannot be destroyed”. Bombs continued to tear through the night sky over London. One surgeon recalled seeing Matron MacManus on her knees in the operating theatre wiping up blood to make way for the next serious cases.

By the war’s end, Miss MacManus was exhausted. She had been a participant in every raw sense in the theatres of two world wars. She longed for Mayo, its peace and healing. In 1946 she retired from Guy’s and in time moved into her lakeside lodge to fish, read and write her memoirs.

And so, many years later, this was the Miss MacManus we came to know. Her escapades with my aunt Julia were never dull. She loved nature and goats became an abiding passion. Once, the pair of them headed out the long road to Belmullet to buy a Billy goat. Storms suddenly burst, roads flooded. Stranded, she used her formidable persuasive charms to find accommodation for the night – a cell in the Garda station – for herself, my aunt and the goat.

In the end she chose to die in Mayo, turning down the offer to end her days in the care of Guy’s. She died in 1978, aged 92, in the Sacred Heart Hospital in Castlebar and is buried in the cemetery adjoining St Michael’s Parish Church in Ardnaree, Ballina. Before her death she had one last request – that locks of her hair be cut off and entwined through the branches of shrubs and trees around Killeaden. So, come spring, birds would use the wisps to build and upholster their nests.

She loved poetry, especially, understandably, the War Poets. I would like to think one of them, our own Francis Ledwidge, in some way inspired her last, strangely beautiful gesture, with his poem, A Soldiers Grave:

Then in the lull of midnight, gentle arms

Lifted him slowly down the slopes of death

Lest he should hear again the mad alarms

Of battle, dying moans, and painful breath.

And where the earth was soft for flowers we made

A grave for him that he might better rest.

So, Spring shall come and leave it sweet arrayed,

And there the lark shall turn her dewy nest

Tom Rowley

This article is based on a broadcast Tom Rowley did for Sunday Miscellany on RTE Radio 1 in November, 2013. Tom worked as a senior reporter and news editor with the Irish Independent newspaper before spending a decade as a press advisor to the late government minister, Seamus Brennan. He lives in Rush in North County Dublin. He is a regular contributor to Sunday Miscellany on RTE radio and An Irishman’s Diary in The Irish Times.

Tom is continuing his research into the life of the late Emily MacManus. He would welcome any information relating to her remarkable life, including memories, photographs, articles or any other material that may be of interest. He can be contacted at: tomjmrowley@gmail.com or by post at ‘Abhaile’, Palmer Road, Rush, Co Dublin.