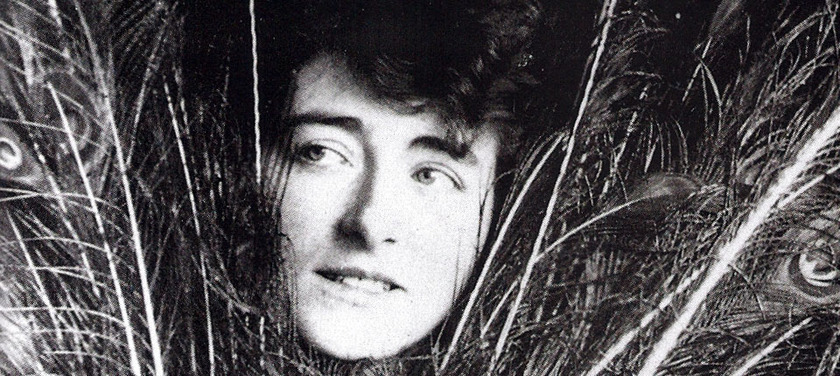

Eileen Gray

Trailblazing Modernist Designer

Today, Eileen Gray, the Irish-born architect and furniture maker is held aloft as one of the most innovative designers of her time. Her secretive personal life means that she is an enigmatic figure about whom our knowledge is often limited. Her stark modern designs and mastery of the ancient Japanese craft of lacquer work, cements her legacy as one of the foremost female designers in history who achieved international acclaim in an often male-dominated sphere.

Eileen Gray was born to an affluent Anglo-Irish family in Brownswood, Co. Wexford in 1878. Although her mother Eveleen Pounden came from aristocracy, she decided to buck tradition and marry a middle-class artist. Eveleen’s rejection of convention was passed onto Eileen and it became a prominent feature of her personal life, as she had numerous relationships with both men and women. Like many wealthy women of the period, Eileen studied at the Slade School of Art in London while living in South Kensington, but she found herself bored by painting and drawing classes. Her introduction to lacquer work at the Victoria and Albert museum was a formative early experience that would lead to her future success. Her artistic training continued in Paris when she moved there in 1902 with two friends. It was only when Eileen moved back to South Kensington to be with her ailing mother that she stumbled upon the lacquer workshop of Mr. D. Charles in Soho. Here, she watched him at work and was given Parisian lacquer contact details. Upon her return to Paris, she began a four-year long collaboration with a Japanese lacquer artist named Seizo Sugawara. 1913 was an important year for Eileen as she exhibited lacquer work at the Salon des Artistes Décorateurs and was commissioned by her first significant client, Jacques Doucet.

Although the breakout of war forced Eileen to return to England for a time accompanied by Sugawara, in 1917 they returned to Paris and were commissioned by Madame Mathieu-Levy to decorate an apartment on the Rue du Lota. Here she hand crafted most of the furniture and designed panels and carpets. This included the now famous Bibendum lounge chair, consisting of two padded tubes encased in soft leather. The predominant material used to decorate the apartment was lacquer, for example, the walls of the entrance hall were lined with hundreds of small lacquered panels from which she was to develop her much revered design, the Block Screen.

A friendship with the architecture critic Jean Badovici, led to the collaborative opening of the Galerie Jean Désert in 1922, an exhibition space and shop. While England and America had a number of female decorators, Eileen was alone in the male-dominated world of Parisian design. In 1923, she created a Bedroom-Boudoir for Monte-Carlo, to be exhibited at the Salon des Artistes Décorateurs. In 1926 the Maharaja of Indore purchased two Transat chairs that Eileen had initially designed for a new architectural project, the E-1027 house in Rochebrune, now declared a National Monument by the French government.

In 1926 she began construction of this house for Badovici on a steep cliff overlooking the Mediterranean. This home has been described as a truly modern architectural model. Its open plan was achieved by the use of both fixed walls and moving screens. Architecture and furniture interacted harmoniously as she cleaved to a logical organization of space. Innovative furniture included her E-1027 bedside table created with steel tubing that could be raised or lowered to a desired height. Much of the furniture in the house could in fact rotate, pivot or bend for ease of use and she used lacquer extensively. During her lifetime E-1027 received little praise, but today it is considered a classic structure in modern architecture, created, incredibly, by a designer with no formal training.

She designed a home for herself at Tempe à Pailla in 1932, but World War II forced her to move inland for safety. This period of isolation led to her becoming a recluse, a status she maintained until her death. Upon returning to Tempe à Pailla she found it looted, along with her flat in Saint Tropez which housed much of her work. Devastated by this, her work during the war was limited. In 1954 she began to construct her third house, Lou Perou near Saint Tropez but shied away from the public eye completely. She lived in her apartment on the rue Bonaparte and continued to design, her work slowly being appreciated via a number of exhibitions in the 1970s. Her death in 1976 was deemed worthy of a French national radio announcement, as the world began to realize what a talent it had lost.

Today, both Ireland and France have made steps to recognize the genius of Eileen Gray. At home, an exhibition in the National Museum of Ireland at Collins Barracks tells the story of her life through examples of her work. These items were acquired from her Parisian apartment upon her death. More recently, a retrospective exhibition at the Centre de Georges Pompidou in Paris highlights her artistic innovation by displaying previously unseen works. This exhibition was opened by President Michael D. Higgins in February of this year and will run until May. In his words, this exhibition provides the intense acclaim that this “magnificent and evocative” Irish designer never fully gained during her lifetime.

Ella Hassett