Fictionalising History - Guest Blog by author Marina Neary

In 1903, at the age of 20, Dubliner Helena Molony (1883-1967) was inspired to join Inghinidhe na hÉireann (Daughters of Ireland) by a speech given by Maud Gonne. Somewhat of a renaissance woman, she engaged in a campaign to compel Dublin City Council to provide meals to the starving children of Dublin, she founded and edited Bean na hÉireann (a monthly ‘woman’s paper advocating militancy, separatism and feminism’ that could count Eva Gore-Booth, Countess Markeviecz, Roger Casement and Patrick Pearse amongst its contributors) and acted on the Abbey stage.

She was a member of Cumann na mBan and, ‘always on the side of the underdog’, she became active in the Labour Movement. During the 1916 Rising, she was one of the Irish Citizen Army that attacked Dublin Castle. She was imprisoned until December 1916 after which she continued her activities in left-wing, nationalist and feminist activism. Post-Independence, Helena began to despair of the manner in which the Free State treated women - ‘their inferior status, their lower pay for equal work, their exclusion from juries and certain branches of the civil service, their slum dwellings and crowded, cold and unsanitary schools for their children’. She became President of the Irish Trade Union Congress in 1937 but was forced into retirement in 1941 and lived in poverty until her death in 1967. A complex and dynamic woman, it could be argued Helena was too revolutionary and idealistic to be contained even by the turbulent era in which she played such an integral part.

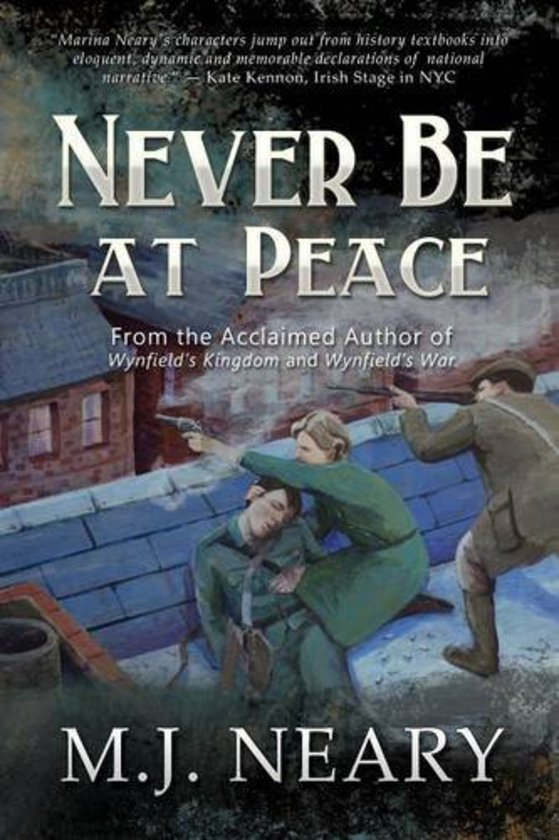

In her novel, Never Be At Peace, Marina Neary fictionalises Helena’s life and here she describes the challenges of taking on the voice of an historical character.

The legacy of Helena Molony has been, unfortunately, downplayed and neglected by historians. I hope with the 100th anniversary of 1916 just around the corner, the obscured figures will be resurrected and illuminated.

I started writing Never Be at Peace in 2011 shortly after completing Martyrs and Traitors: a Tale of 1916 which featured the political and intimate misfortunes of Bulmer Hobson, another figure whose contributions to the Irish nationalistic movement had been downplayed on the account of his opposition to the Easter Rising. According to some sources, Hobson and Molony had been more than former comrades torn apart by an ideological rift – they had been lovers. They came from two different worlds. He was an upper middle-class Protestant from a stable family in Belfast. She was a quintessential lower middle-class Catholic girl from Dublin, an orphan to boot. After finishing Martyrs and Traitors, I realised that I was not finished telling the story of Hobson’s first love. A separate novel had to be written.

Historical literature abounds with tales of troubled revolutionary actresses who defied the convention. Who can resist a pugnacious girl who was arrested for throwing rocks at the portrait of King George, took part in an armed rising and who tried to dig her way out of prison with a metal spoon? Sometimes I half-jokingly say that Helena Molony is Ireland’s Cinderella. Indeed, there are some undeniable parallels. Helena had a wicked stepmother and a fairy godmother figure – the indomitable Maud Gonne who helped launch her theatrical career and propelled her to the new level of prominence in nationalistic circles. Helena even had a potential Prince Charming in the face of Bulmer Hobson, though that relationship was not meant to have a happy ending. Helena’s golden carriage turned back into a rotting pumpkin a little too soon. Personal disappointments and losses aside, her dreams for a free Ireland did not transpired as she had hoped.

One of the reasons why I didn’t write a straightforward biography on Helena Molony is because there isn’t enough material to work with. Nell Regan was fortunate enough to interview some of the people who knew Helena personally but alas, so much documentation has been lost. Most of Helena’s photos from her days on stage perished in the fire at the Abbey Theatre. Her image had to be reconstructed from the episodic accounts and references of her surviving contemporaries.

When writing historical fiction with limited amount of primary sources on hand, it’s not just about filling the gaps with whatever comes to mind. It’s about making educated guesses and choices that will honour the integrity of the era. While the revolutionary women of that era acted somewhat outside social norms, there is a limit to how much freedom a novelist can take. Historical fiction is like a minefield. You have to be wary of anachronisms. Believe me, I’ve read many manuscripts featuring ‘forward-thinking’ heroines who act not like they are 10 years ahead of their time but a few solid centuries. I’m referring to scenes where a medieval maiden tosses her hair, rolls her eyes and declares that ‘she has a mind too, and will not be treated like a piece of meat.’ In short, shop girls from Edwardian Rathgar do not behave like reality TV stars. How would an unmarried woman of the late Victorian era deal with an unplanned pregnancy? Even Maud Gonne, with her penchant for defying conventions, raised her illegitimate daughter Iseult in a convent and then presented her to the polite society as her niece.

One of the most surprising conclusions of my research was that women in 1908 appeared to have more freedom and moral latitude than in 1938 after De Valera’s constitution that hurled Ireland into a sort of theocratic patriarchy. In light of the new cultural shift, Helena suddenly fell out of favour. Prone to alcoholism and angry outbursts she became a persona non grata. Her penchant for violent melodrama that made her such a compelling revolutionary figure suddenly made her less than desirable in the context of new culture that encouraged obedience and domesticity in women. The nature of her relationship with Dr. Evelyn O’Brien, a psychiatrist seventeen years her junior was subject to speculation. Some historians insist that Helena was bisexual, and Dr. O’Brien was her romantic partner. So when she started falling out of public life, nobody protested.

The novel features an ensemble of other prominent women of the nationalistic movement such as Countess de Markiewicz, Dr Kathleen Lynn and Lily Connolly. In the words of Pearse, ‘Ireland unfree shall never be at peace’, but it seems that the war continues even after the last shot had been fired.

Marina’s novel Never Be At Peace is available from www.amazon.com